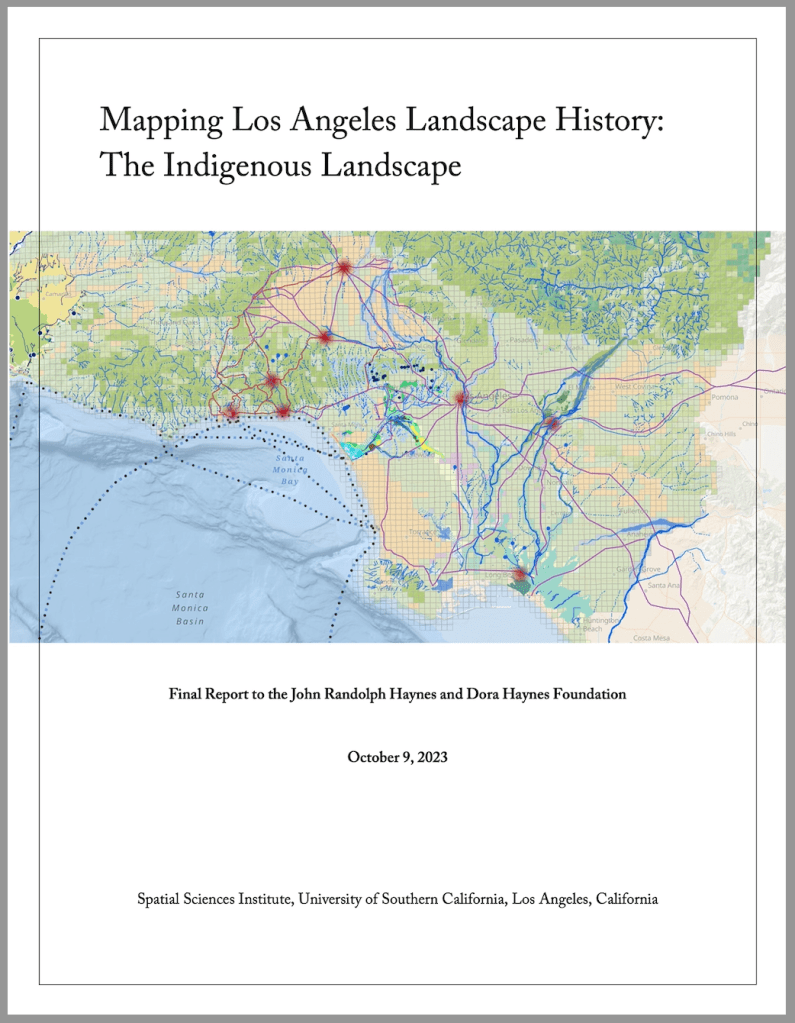

The final report for the 2020-2023 historical ecology study funded by the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation can be downloaded here on October 9, 2023.

Longcore, T. and P. J. Ethington, eds. 2023. Mapping Los Angeles Landscape History: The Indigenous Landscape. Report to the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. Spatial Sciences Institute, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

The report also includes an interactive website in the StoryMap format, which can be accessed here:

Please note that StoryMap format is designed for desktop and laptop computers and may not function with all mobile devices.

Editors

Travis Longcore & Philip J. Ethington

Contributors

Jesus Alvarez (Tataviam)

Tataviam Fernandeño Band of Mission Indians

Anthony Baniaga

UCLA Herbarium, University of California Los Angeles

Danielle Bram

Center for Geospatial Science and Technology, California State University Northridge

Jonathan Cordero (Ramaytush Ohlone/Chumash)

Spatial Sciences Institute, University of Southern California

William Deverell

Department of History, University of Southern California

Philip J. Ethington

Department of History and Spatial Sciences Institute, University of Southern California

Devlin Gandy

Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge

Travis Longcore

Institute of the Environment and Sustainability, University of California, Los Angeles

Sean Lyon

Department of Biological Sciences, California State University Los Angeles

Beau MacDonald

Spatial Sciences Institute, University of Southern California

Suzanne Perlitsh

Department of Geography, California State University Long Beach

Andy Salas (Kizh)

Kizh Nation: Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians

Matthew Teutimez

Kizh Nation: Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians

Matt Vestuto, (Barbareño/Ventureño Chumash)

Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival

John P. Wilson

Spatial Sciences Institute, University of Southern California

Scott Winslow

Department of Geography, California State University Long Beach

Eric M. Wood

Department of Biological Sciences, California State University Los Angeles

Natale Zappia†

Department of History and Institute for Sustainability, California State University Northridge

† Deceased April 2023

Principal Investigators

PI: Ethington

Co-PIs: Alvarez, Bram, Cordero, Longcore, MacDonald, Perlitsh, Teutimez, Vestuto, Wilson, Wood, Zappia

Executive Summary

As projects emerge to protect, restore, and enhance natural landscape in the Los Angeles region, attention turns to the historical landscape for understanding, inspiration, and context. Descriptions of the historical landscape patterns and function have led to a conclusion that this landscape and region cannot be understood without listening to the stories of Indigenous people who managed this land and thrived for thousands of years before the arrival of European settlers. In this project, our team blended geographers, historians, and biologists with representatives of three tribes — Chumash, Tataviam, and Gabrieleño — to undertake a collective investigation of six village sites and their natural features as they would have existed before European arrival. The resulting effort, funded by the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation since 2020, blends different approaches to understanding and describing the landscape to produce a set of parallel products that describe the six village sites in detail and provide detailed maps of the natural environment, its flora and fauna, and tools to understand its influence into the modern era for the region.

Stories about each place and its importance have been recorded by tribal representatives for Humaliwo (now Malibu), Siutcanga (Encino), Achoicomenga (San Fernando), Yaanga (downtown Los Angeles), Shevaanga (Whittier Narrows), and Povuu’unga (Long Beach). Videos of these in-site discussions have been compiled to and are presented in a map-based website. (Leads: Alvarez, Cordero, Gandy, Teutimez, Vestuto, Zappia)

Together, the team pursued seven additional investigations designed to provide insights on these places and the region from different disciplinary lens and using different methodological sources and approaches. These provide standalone resources to understand the past and current landscapes of the region and were also synthesized into highly detailed three-dimensional maps of the vegetation and natural features of each village area.

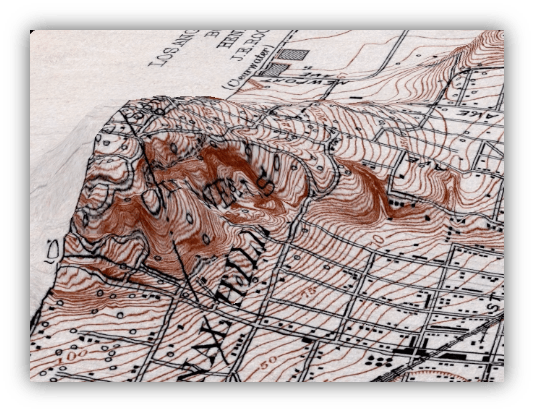

Topographic reconstruction. Topography is fundamental to understanding landscapes, but the Los Angeles region has been highly modified both for water management and to accommodate urban development and transportation infrastructure. Historical maps of topography exist but do not provide data in a form that can be used for modern models and visualizations. Our team used sophisticated image recognition tools and an international volunteer effort to extract the elevations of over fifteen million individual points located on historical topographic maps to create the first-ever digital elevation model of the Los Angeles Basin from Ventura County to Orange County. (Lead: Perlitsh)

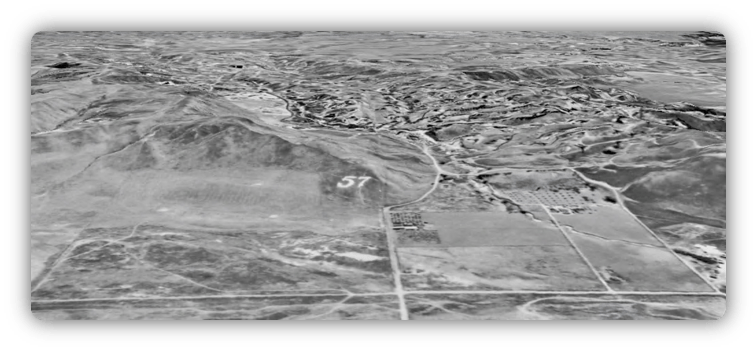

Aerial photograph mosaic. Although aerial photography was started consistently in the 1920s in Los Angeles, images from that era are extremely useful in visualizing and understanding landscape features that were present before urbanization. A full-county set of images from 1928 had been previously scanned, but not oriented so they could be placed on a map and compared with contemporary features. Our team created a mosaic of these images, located them in geographic space, and linked them together into a continuous map image layer encompassing the Los Angeles Basin, Santa Monica Mountains, and into the foothills of the valleys covering 1,745 square miles. (Lead: Bram)

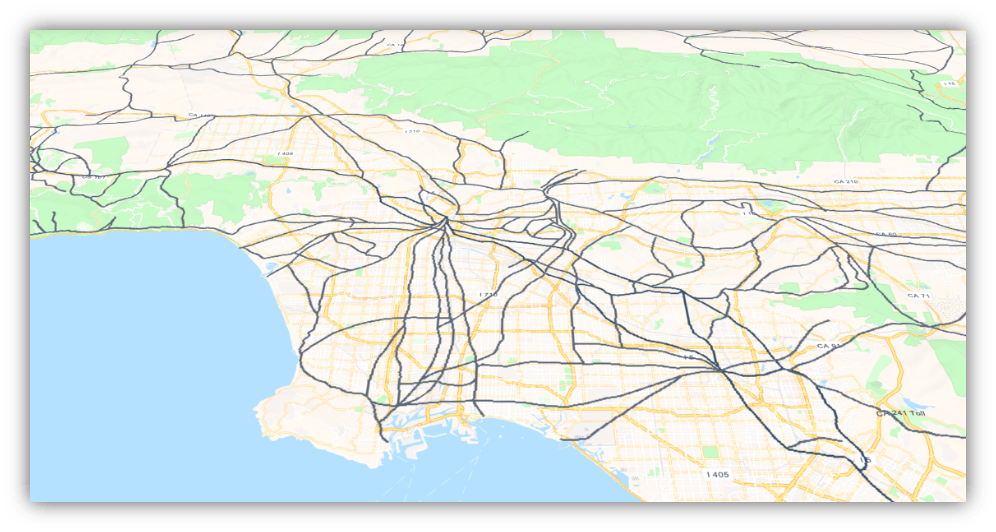

“Blue line” streams and water bodies. Our team digitized all the rivers, lakes, streams, wetlands, ponds, and other water features on the 1920s U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps. These lines can now be overlaid on contemporary maps to reveal the location of buried streams, filled wetlands, and water features that have persisted through time. (Lead: Longcore)

Indigenous trade networks. The pathways that linked together people and resources within the Los Angeles region and to points across the entire southwest are easily forgotten in a city crossed by freeways. Drawing on extensive archival sources, newly digitized maps, sketches, Indigenous place names and histories, and other texts, our team constructed a synthesis map of the pre-European trade and movement networks across the region. (Leads: Ethington, Alvarez, Gandy, Teutimez, Vestuto)

Least cost pathways. To complement the map of trade networks derived from archival sources and Indigenous knowledge, our team also modeled the easiest routes for an individual to walk over the topography of the region from location to location. The most common routes resulting from this approach provide additional data to interpret the pathways found on historical maps and suggest that use of some routes is nearly inevitable based on topography, such as the route that would become Ventura Boulevard and then the 101 freeway through the San Fernando Valley. (Leads: MacDonald, Longcore)

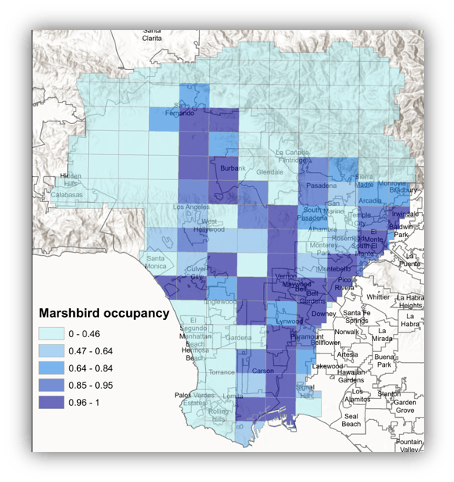

Historical bird distributions. The nature that would have been found across the Los Angeles region has been altered dramatically by urbanization. To understand what bird species would have been found at our focal villages and what species have declined and increased, our team used nest location records from museum collections and our previously developed potential natural vegetation map to predict historical bird species composition. Some groups of species have declined nearly to extirpation, such as those associated with grassland, while others have been more resilient in the face of urbanization. (Leads: Wood, Lyon)

Oak, walnut, and elderberry habitat models. Plants that provide food resources are important to Indigenous food systems and culture. The team selected a set of such plants, including several oak species (coast live, valley, mesa, and scrub), California black walnut, and blue elderberry for our biogeographers to investigate. Using environmental data, including historical topography developed by the project in some areas, and current distributional data for these species, habitat models were developed with machine learning approaches that suggest the historical distributions of these species, even in areas where they have been eliminated today. (Leads: Longcore, MacDonald, Teutimez)

Remnant native plants. Notwithstanding several hundred years of urbanization, some of the plants native to the region may survive, even in highly developed neighborhood. To investigate this possibility, surveys for spontaneous vegetation (weeds) were undertaken along sidewalks in areas that supported a range of different vegetation types historically. Some native plants persist, and those located were consistent with the mapped historical vegetation type, supporting the landscape descriptions developed for the region. (Lead: Baniaga)

This project is unique because a commonly shared, detailed map of the historical ecology—the flora, fauna, hydrology, and landforms, that evolved within Southern California’s Mediterranean climate over millennia and supported human populations for 9,000 years, has never been developed. Individually and cumulatively, the results of this research are vital resources to all regional and local planning efforts involving sustainability, habitat restoration, and preparing for climate change. This project is also unique also because four of its co-Principal Investigators are members of the Indigenous peoples of the Los Angeles Basin (Gabrieleño, Tataviam, and Chumash).